Case Study in Documentation Usability - Django vs. Flask/SQLAlchemy

When I’m evaluating new open source projects, there are a few things I look for. I look for how many stars they have on GitHub. I look at their issues in GitHub. If you are not on GitHub, I’m basically not interested. Finally, I look at their documentation. But how do you know if the documentation is any good? What makes good documentation, anyway?

Documentation Usability

Documentation can be exhaustive and still not ultimately useful. Documentation usability is the idea that documentation ultimately needs to help users solve their problems. Given a task to be done, how quickly and correctly can the documentation enable the user to complete their task?

The first thing you need to realize is that search is the interface for your documentation. You might get users to read a high level overview of the project when they are first starting out, but with rare exception no one is reading the entire documentation front to back for anything remotely complicated. Instead, they will search when they have a question. Usually using Google, not some crappy search functionality inside your documentation.

Your first challenge then is finding out what terminology your users are using. Importantly, you cannot assume that they will use your invented vocabulary. Your project is part of the entire ecosystem of tools they already use. Your best bet is to use existing terminology.

Also, users should know at all times where they are in the documentation relative to the whole, and relative to where they were previously. You want them to be able to quickly find related topics.

Case Study - Django versus Flask/SQLAlchemy/Alembic

Django is a framework renowned for their excellent documentation. It’s a swiss army knife project that includes lots of functionality. A common alternative is a collection of projects, headlined by Flask, SQLAlchemy and Alembic. The documentation for the second set of projects is better than most. It’s pretty exhaustive. But it’s not very usable.

From the Django Guide to Documentation:

We place a high importance on consistency and readability of documentation. After all, Django was created in a journalism environment! So we treat our documentation like we treat our code: we aim to improve it as often as possible.

This dedication to continuous improvement of the documentation is evident in some common use cases.

Task: SQL IN clause queries

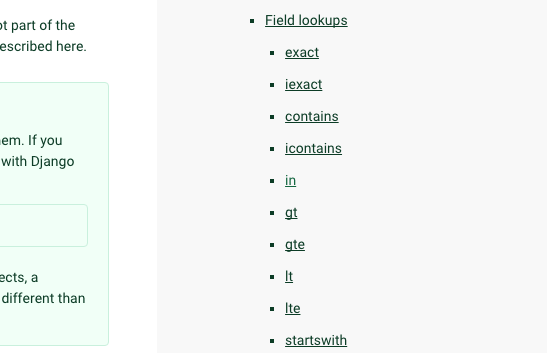

One common task in both ecosystems is accessing a database. Further, there is a common (if not core) use case where you want to query a database by a list of record IDs. If you Google for Django query in list, the first hit is the Django documentation, and there is a sidebar with the “in” clause called out:

If you search for SQLAlchemy query in list, you get five Stackoverflow answers before you see their official documentation. The first hit does not contain a correct answer. The actual documentation hit takes you a nebulously titled page, “API”. The table of contents does not contain anything at the granularity of individual topics on that page. Searching the page for “in” is of course fruitless. There is specific documentation for this feature, but it does not come back in the first few pages of Google results. Even if you find it, it does not include a specific code example.

Task: Modify records when they are saved

If you Google for Django on save, the first hit is Stackoverflow. The second hit a specific documentation for what happens when a record is saved. That links directly to how to over-ride a method called post_save.

If you Google for SQLAlchemy on save, you see three identical results for three difference versions of SQLAlchemy. In each case, you get a page for ORM events, which you basically need to read the entirety of to understand. There are nebulous sidebar links for “Mapper Events”, “Session Events” and “Query Events”, but those are not terms that make immediate sense to me, without reading a bunch of other documentation.

Task: Redirecting HTTP to HTTPS

If you Google Django redirect HTTPS, the third result is a bug report where someone went back and added a link to the canonical feature for this, SECURE_PROXY_SSL_HEADER. Great example of paying attention to what users are searching for.

If you Google for Flask redirect HTTPS, you also get a bug report as the first hit. There is some discussion, but not solution, at least for the case where something like Flask-admin is doing the redirect. But there actually is a documented solution, though it does not show up in the Google results.

Take aways

- Exhaustive documentation is not necessarily useful documentation

- Take time to write in your user’s vocabulary

- Find out what they are actually searching for

- Update old documentation to point to new solutions