What is strategy, versus vision or mission? Is a business goal a strategy? It’s hard to tell whether a strategy will be successful, up front. When you’re creating a strategy, it can seem impossible to achieve. In retrospect, a good strategy seems like it was obvious, even though it was anything but.

In this post, I’m going to use the rough outline of a case study, to root the conversation. Because this is such a well know case study, the strategy may seem obvious in retrospect. Having been alive and following this company during this period, I can attest to the fact that it was not obvious what the strategy should be, or that it would be successful.

Case Study: Apple in 1997

In 1997, Apple was on the brink of bankruptcy – in fact they had about 90 days of runway left. Expenses were high, revenue was flagging, and market share was down. These trailing indicators were not the reason the company was under-performing, though. Steve Jobs came back, and had to decide how to turn the company around, starting with diagnosing why the company was under-performing.

Jobs’ diagnosis was that the company had stopped innovating:

When I left Apple ten years ago, we were ten years ahead of anybody else. It took Microsoft ten years to copy Windows. The problem was that Apple stood still. Even though it invested cumulatively billions in R&D, the output has not been there. People have caught up with it, and its differentiation has eroded, in particular with respect to Microsoft. And so the way out for Apple – and I think Apple still has a future; there are some awfully good people there and there is tremendous brand loyalty to that company – I think the way out is not to slash and burn, it’s to innovate. That’s how Apple got to its glory, and that’s how Apple could return to it.

This seems obvious, in retrospect. It’s also deceptively simple – who does not want to be innovative? It is simple, but it’s not easy. How did Apple under Jobs (again) turn this diagnosis into a strategy, and how did they execute on it?

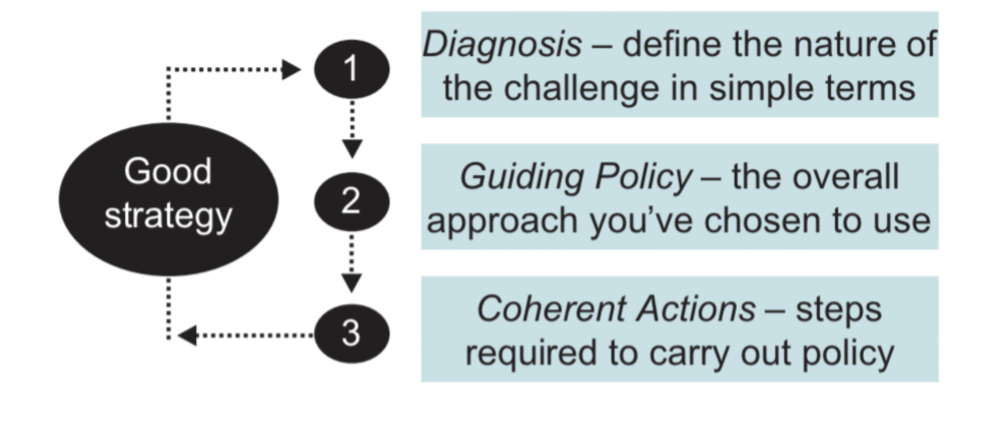

I’m going to borrow a strategy format from Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters by Richard Rumelt, to illustrate.

Apple Strategy 1997

Our primary business challenge is that was are failing to

innovate. Microsoft has caught up with MacOS, while we have

been standing still. We need to leverage our excellent people,

and our brand loyalty, and innovate our way back to

differentiated products.

Our current market share in personal computing is 3.8%, down

from 10% just 5 years ago.

Guiding Principles:

1. Focus our efforts on fewer things

2. Exploit our design and engineer excellence by creating

delightful products

3. Exploit our brand loyalty by focusing on high margins

Actions:

1. Cut our workforce by 30% to increase cashflow

2. Cut current product roadmap by 70% to focus resources

on a few innovative investments

3. Buy NeXT to be the foundation of an innovating

next-generation operating system

In the following years, Apple released the G3 Mac (1998), which had a radically delightful design aesthetic. It was a hit with the market. It released the iPod (2001), which was the first product in the category to be successful, due to a combination of excellent design and brand loyalty. Apple also released Mac OSX (2001), a technically innovative and aesthetically beautiful operating system. None of these product decisions were obvious at the time, but together they comprised a series of market hits that continued though the iPhone (2007), and turned the company around. Apple was successful because they focused, and they executed.

What is Strategy?

Let’s break down this strategy, using the format in the Rumelt book. The hypothetical Apple strategy is a short, written document that diagnosis the problem, defines how the company will focus efforts, and contains specific actions. This matches Rumelt’s definition of a good strategy:

The kernel of a strategy contains three elements: a diagnosis, a guiding policy, and coherent action. – Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters

The hard parts are making the correct diagnosis, making the difficult decisions to focus and then actually executing successfully. I love this format because it’s prescriptive about what a good strategy looks like. It allows you to get to the heart of the actual strategy work immediately.

Diagnosis

Steve Jobs’ diagnosis was that the company has failed to innovate. That did prove to be a decisive challenge to the business, that once solved, did lead to success. That’s not to say that it was the only strategy that would have been successful. This diagnosis is a good example of what Rumelt calls a key insight.

The first step of making strategy real is figuring out the big ‘aha’ to gain sustainable competitive advantage—in other words, a significant, meaningful insight about how to win.

The book tackles strategy at the company level. The diagnosis should identify the most decisive challenge to the business, and also the cause of the challenge. It’s OK if the challenge is written in terms of the business, and not as a user problem. The diagnosis simplifies the problem space down to one critical factor.

There is no silver bullet to coming up with the right diagnosis. You might start by asking “five whys” about a few important business problems. Perhaps they will lead back to the same root issue. But in the end, picking correctly requires an intuitive leap.

At the core, strategy is about focus, and most complex organizations don’t focus their resources. Instead, they pursue multiple goals at once, not concentrating enough resources to achieve a breakthrough in any of them.

At the company level, there should be one diagnosis, not many. The ideal strategy focuses resources on a small set of actions, and those actions exploit a strength, or take advantage of a weakness.

Many bad strategies are just statements of desire rather than plans for overcoming obstacles.

You should gather data and see if it backs up the diagnosis. What is a single piece of data that makes the most compelling case for the diagnosis?

Don’t be tempted to use the data to set a goal at this stage; a goal itself is not a strategy. The diagnosis should not read like a wish, or a hope.

Finally, the diagnosis needs to tell how the challenge will be overcome.

Guiding Principles

Apple decided to focus on fewer things, and leverage some key strengths versus the competition. Focus itself may not need to be stated – focus is assumed as part of Rumelt’s definition of a good strategy.

Good strategy requires leaders who are willing and able to say no to a wide variety of actions and interests. Strategy is at least as much about what an organization does not do as it is about what it does.

Guiding principles inform how the business will make trade-offs. How will you choose between different actions? This helps make sure that the actions are coherent, together. It also allows the decision making to scale across the organization. Guiding principles are a good opportunity to maximize existing strengths.

Actions

Apple took concrete action, some of them, like layoffs, being quite difficult. The actions were coherent with each other; they all followed a theme, and were mutually reinforcing.

A good strategy includes a set of coherent actions. They are not “implementation” details; they are the punch in the strategy. A strategy that fails to define a variety of plausible and feasible immediate actions is missing a critical component.

Actions need to be both specific and achievable. It’s notable that the actions were not building the G3, the iPod, and OSX. That would be far too specific. These specific products were likely not envisioned for a year or two after the strategy was defined. However, you can imagine individual teams at Apple, like the desktop Mac hardware team, coming out of layoffs with a mandate to create innovative desktop computers, leveraging Apple’s design aesthetic strengths. This is how strategy flows down across the company.

Multiple Levels: Make it a team sport

The book is short on this topic. By focusing on company level strategy, it fails to address how strategy is distributed. Indeed, one of the main points is that company strategy should have a singular focus. At the same time, a large company will in fact do many things at once. It doesn’t actually make sense to focus 100% of a company on one thing. In the best case, this looks like local strategies that align to the company strategy, and being prescriptive without being specific about what bets the teams in the company should make.

Strategies focus resources, energy, and attention on some objectives rather than others. Unless collective ruin is imminent, a change in strategy will make some people worse off. Hence, there will be powerful forces opposed to almost any change in strategy. This is the fate of many strategy initiatives in large organizations.

Depending on whether the customer of the sub organization is internal or external, it starts to make more sense to phrase the local diagnosis in terms of the customer. In this way, each organization and sub-organization can have their own strategy that aligns to the company strategy. At the team level, the actions are going to be much more concrete than at the company level.

There are times of year that are naturally more strategy focused. But setting strategy is something you should be doing all the time, as a leader of an organization. Instead of thinking about it like a once-a-year waterfall process, think about it more like cyclical continuous refinement.

What is the difference between strategy and vision?

There is a lot of stuff that comes after the strategy. It’s common to refresh strategy yearly, and then do headcount planning and potentially reorganize teams. That’s a complex topic, on its own. Strategy is sometimes conflated with vision and mission, although they are actually separate. Roadmap planning in another common follow-on from strategy work.

Despite the roar of voices wanting to equate strategy with ambition, leadership, “vision,” planning, or the economic logic of competition, strategy is none of these. The core of strategy work is always the same: discovering the critical factors in a situation and designing a way of coordinating and focusing actions to deal with those factors.

Strategy is upwards facing. It’s about making a compelling case to your leadership that you have a plan which will lead to business success. For an executive, the leadership audience is the board of directors. For a director, it’s the executives, etc. Strategy also encompasses work from many teams, either an entire company, or an entire sub organization.

Vision is downwards facing. It’s about making a compelling case to the teams and individuals that they should be excited about the work. It’s about inspiring builders and creative workers. It’s about connecting the work to the user. The audience can be a single team.

Defining a vision should be done after creating a strategy, for the simple reason that strategy informs what to focus on. It’s true that you can’t make sure a strategy is achievable without concrete actions, and eventually estimates. But, the greater risk is defining a vision and roadmap that do not address the critical business challenge. After creating a strategy and defining a vision, the next step is to start building a roadmap with high level estimates.

Example Template

A hallmark of true expertise and insight is making a complex subject understandable. A hallmark of mediocrity and bad strategy is unnecessary complexity—a flurry of fluff masking an absence of substance.

[NAME] Strategy [YEAR]

[LINK TO PARENT STRATEGY]

Out primary business challenge is [THREE SENTENCES]

[BACK IT UP WITH DATA]

Guiding Principles:

1. Exploit our [STRENGTH] by [DOING X] instead of [DOING Y]

2. Exploit our [STRENGTH] by [DOING X] instead of [DOING Y]

3. Exploit our [STRENGTH] by [DOING X] instead of [DOING Y]

Actions:

1. [THREE SENTENCES] [ACHIEVABLE GOAL]

2. [THREE SENTENCES] [ACHIEVABLE GOAL]

3. [THREE SENTENCES] [ACHIEVABLE GOAL]

The key stages in drafting a strategy are all around feedback. First, get feedback from your peers. You all need to be on the same page about the primary business challenge, and the most important actions. At every review, you want to answer the question, “would I fund this initiative”?

Then, get feedback from your leadership team. Ask the to be brutal. Get feedback both 1:1 ahead of time, and in a group setting. Plan to do multiple rounds of edits. Ask how this relates to other strategies.

Finally, incorporate feedback from your organization itself. This often looks like the addition of actions that line up to the strategy. There is a danger in both communicating the strategy before you have upwards alignment, and also waiting until the strategy is locked to ask for additional actions. You need to find a balance. Give teams permission to go off and create their own strategies that line up to this.