In software, there is a term of art for work that’s required to “keep the lights on”, aka “KTLO”. It’s defined as work that’s NOT adding new product value. It includes traditional “on-call” activities, such as responding to pages, and remediating outages. It also includes fixing bugs, and resolving customer requests. A third subset of KTLO is doing required migrations to new versions of a platform, framework, or operating system.

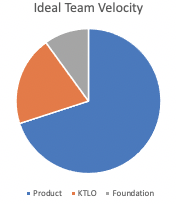

KTLO is not the same as technical debt. Technical debt is typically thought of as an existing backlog of stuff to fix. KTLO is the work that you’re actively doing all the time, just to tread water at your current technical debt level. KTLO is also distinct from refactoring work. Refactoring is certainly important, but I’m going to label that work “Foundational”, i.e. work to reduce KTLO. “Product” work is the final bucket of work. Together, these tree classifications of work account for all engineering velocity.

What is a “bad” level of KTLO?

Getting to zero KTLO is not the goal. Some level of maintenance will always be required — think security patches, or even just migrating to new internal platforms in a medium sized company. The only way to have zero KTLO is to never change anything, including fixing the site if it’s down. In any case, zero KTLO would be the wrong trade-off between the amount of effort to “bullet proof” everything, versus adding more value.

I’m going to arbitrarily throw out 20% as a healthy KTLO rate that most teams should aspire to. This comes from a general rule of thumb that I have seen many teams at many companies coalesce on. Namely that 80% of the roadmap should be product led and prioritized, and 20% should be engineering led and prioritized.

At the same time, I’ve seen first-hand that 30% KTLO is around where a team starts getting stressed. 40% seems to be a breaking point, where it starts showing up as a top contributor to attrition. Just recognize that whatever the level of KTLO is, this is a tax you’re paying on engineer velocity for other stuff.

Why it gets bad

How do you get to the point where a product requires a high level of KTLO work? One prioritization decision at a time 😉

It’s easy to blame product management for these incentives. “I would love to refactor this thing, but my product partner just wants to add more value!” But, that’s not fair. Let’s play five questions:

- Why do I have to prioritize user value? Because product values it, and they own prioritization for the team.

- Why does product prioritize user value? Because that’s what they are incentivized on.

- Why does the company incentivize user value over other stuff? Because the market rewards growth.

- Why does the market reward growth? That is literally how the stock market works.

- Ok, but why are you beholden to the stock market? That’s the deal you make when you go IPO.

This is also unfair. In practice, I see engineers themselves prioritize user value. No one (for functional equivalents of zero people) wants to work on code that they did not write. They want to re-write it, first. Otherwise, it’s not exciting. Company culture can exacerbate the problem, if it does in fact reward new development over maintenance or foundation work. You should fix that.

Fix the Incentives

Personal finance analogy time. Adding new product value like like buying a stock. You’re taking a bet, hoping for top line growth. Refactoring something is like buying a bond. You’re more sure it will be valuable, but the upper bound of the magnitude is lower. Killing existing stuff is like paying down debt. You’re 100% certain it’s valuable, and it’s going to free up resourcing in the future to invest in other things.

It’s relatively easy to measure the impact of delivering new product value. Users, and internal stakeholders, can see the working product. The company likely has people and an apparatus whose job it is to measure whether the product value is also generating revenue. For accounting purposes, your company classifies engineering salaries as R&D. They actually get a partial tax credit for the portion of software engineer salaries that goes to new product development.

It’s less common to be able to measure the value of KTLO, or Foundational work. When your team goes into hero mode and puts out some fires, they are adding value by keeping the product running smoothly. But, they are also costing the company time and money, namely their salaries. This “routine maintenance” does not count for tax credit purposes. Because your company is already separating salaries for new product development and KTLO into buckets, I recommend that you measure Foundational work as reducing the nondeductible portion of the pie.

For accounting purposes, how many dollars your company spends on the “new user value” part of software development, divided by total revenue, is called R&D efficiency. It’s another common business measure related to KTLO. Notice that you can more of less ignore the cost of KTLO, as long as you’re generating a lot of revenue. That has also been my anecdotal experience of various companies culture’s around KTLO — it only becomes a focus when you stop growing revenue.

Eventually, every company will stop growing. You can’t hire your way out of KTLO, forever. The sooner you can start talking about the impact of reducing KTLO in terms that the business understands, the more you will be able to incentivize it properly.

How to fix it

Beyond incentives, you really need to be able to measure KTLO load, in order to demonstrate the impact of reducing it. One way to measure it would be for everyone to track their time, and categorize time as KTLO vs not. But, virtually no one is going to do that. Also, any measurement could introduce its own perverse incentives, such as mis-reporting time spent to make it look like you’re reducing KTLO.

For some sub-types of KTLO, you could measure things like number of pages, outages, or P0 bugs. You still have to be aware of the perverse incentives issue. You could also measure total time spent on non-KTLO stuff, such as total JIRA ticket volume, minus the KTLO specific tickets.

In the end, I’ve found that simply asking folks what percent of their team’s time is spent on KTLO is fairly accurate. At least, people on the same team can roughly agree, and estimates separated by time tend to come back very similar.

However you measure it, you then want to set a goal. What’s is a good level of KTLO? Again, 20% is a common rule of thumb. Once you have a goal, you want to identify work that can reduce KTLO.

In general, fixing bugs will not reduce KTLO by itself. If you burn the bug backlog down to a point where you are spending less time than you otherwise would have fixing bugs, THEN you have reduced KTLO (at least until it builds back up). The key piece there is that you would otherwise be fixing a substantial number of bugs. If you rarely fix bugs anyway, reducing the bug count does not save KTLO, although it’s a good idea for quality reasons.

This can be counter-intuitive, and can result in teams spending a lot of effort on something that does not actually reduce KTLO load. For that reason, I recommend killing things as the primary method of reducing KTLO. Fewer features, and less code, generally mean less KTLO. The highest value targets are going to be things with a lot of complexity, but relatively business value.

Another clear win for KTLO is automating stuff that you would normally be doing manually. Again, you need to double-check that the team is actually doing the manual work today, versus ignoring it.

No matter what Foundational work you end up doing, you should circle back afterwards and measure that it actually reduced KTLO.