In the context of business and organizations, escalations are when more people are brought into a decision to resolve an issue.

Note: no fictional characters were harmed in the writing of this blog post.

Example Escalations

What the organization structure looks like dictates how to properly escalate an issue. Different situations call for different types of escalations.

Simple Escalation: The Easy Case

Sometimes escalation looks like breaking a tie.

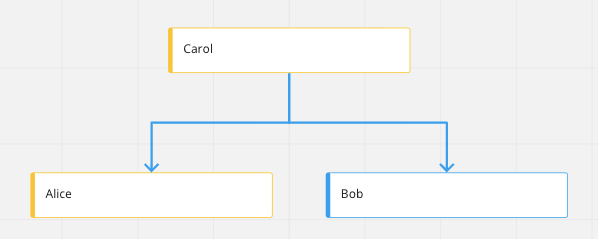

Alice and Bob are engineering managers in different parts of the company. Bob is asking Alice and her team to implement a dependency, like single sign-on functionality. This is a requirement for a feature that Bob’s team is building, and they cannot do it themselves. Alice’s team has a lot on their plate right now, and can’t commit to something new. Alice and Bob end up involving Carol, the VP of engineering, to help make the decision.

This escalation is made easier by the fact that Alice and Bob report directly to Carol.

- Alice and Bob probably have good context on what each other is working on

- Alice and Bob probably have a good relationship with each other

- Carol can probably make the prioritization decision herself

Single Escalation: Sending up a Flare

Sometimes escalation looks like pulling the cord in an assembly line.

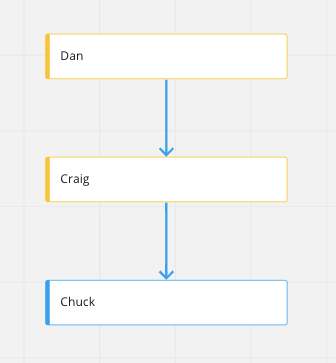

Chuck’s team is understaffed, and he wants to hire people. But, he needs approval. Chuck escalates to his manager Craig. Craig thinks about moving people around in his organization but decides to hire instead. Craig also needs approval for hiring, so he escalates to his manager Dan.

This escalation is also fairly easy. Chuck cannot resolve the issue on his own, so he has to escalate. Dan can approve new headcount directly. Why is this relatively easy?

- Craig and Dan probably have good context

- Chuck, Craig, and Dan probably all have good relationships with each other

- If the issue cannot be resolved, Craig and Dan are only disappointing their direct reports

Double Escalation: The Common Case

Sometimes escalation looks like a ladder.

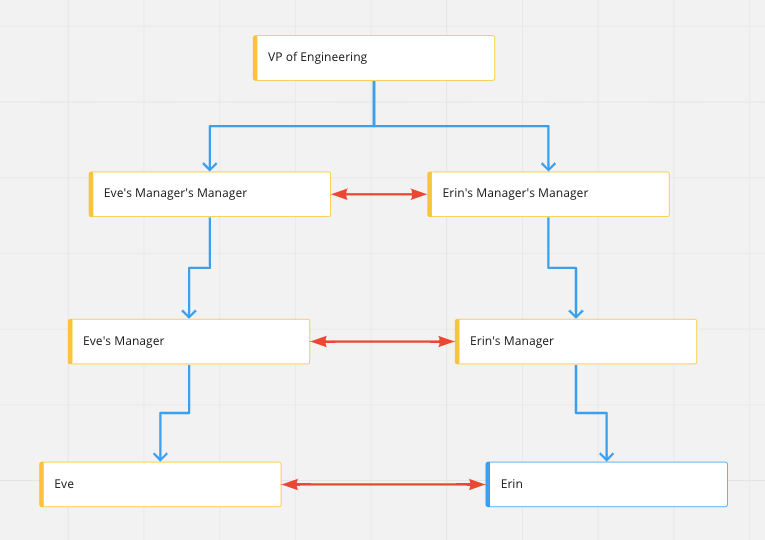

Erin and Eve lead teams in different departments. Erin’s team is writing a new email product. She wants Eve’s team in the platform organization to implement an IMAP service. Eve’s platform team is working on a multi-year strategy to simplify the set of platforms that they own. They are looking to reduce complexity, not add it!

Things get more complicated if two parties in different parts of the organization need to be brought in. These are more likely to involve competing priorities, egos, and differences of opinion.

- More stakeholders will probably be involved in the decision making because it involves high-level strategy

- Because of the distance between the teams in the organization, and also because of the levels of escalation, individuals are less likely to have good context

- The two teams don’t share any management structure; in the worst-case scenario, this could be escalated up to the CEO

This is the first scenario where hesitation to escalate comes into play. No one wants to escalate something to their boss, if they can solve it themselves. As various parties in the chain grapple with this, each is incentivized to broker a compromise themselves. Every link in the chain will attempt to “short-circuit” the escalation, by talking to their partner in the other side of the chain. For this reason, the worst-case escalation to the CEO should only happen if the situation is otherwise unresolvable.

This type of escalation can take a lot of time. Each step up in the ladder will likely discuss the issue, whether it’s over email, Slack, or in person. Any conversation will involve some lag time, especially scheduling and waiting for a meeting. Because of the importance of context, and also the need to compromise, one on one conversation is needed.

How to Escalate

So, how is something escalated properly? First, let’s look at an example of a bad escalation.

Dirty Escalation: Making Frenemies and Pissing off People

Sometimes escalation looks like Godzilla stomping on your city.

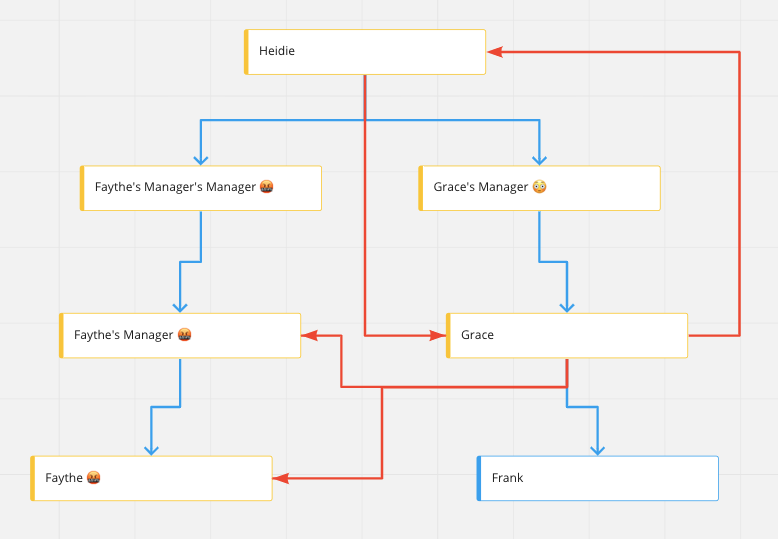

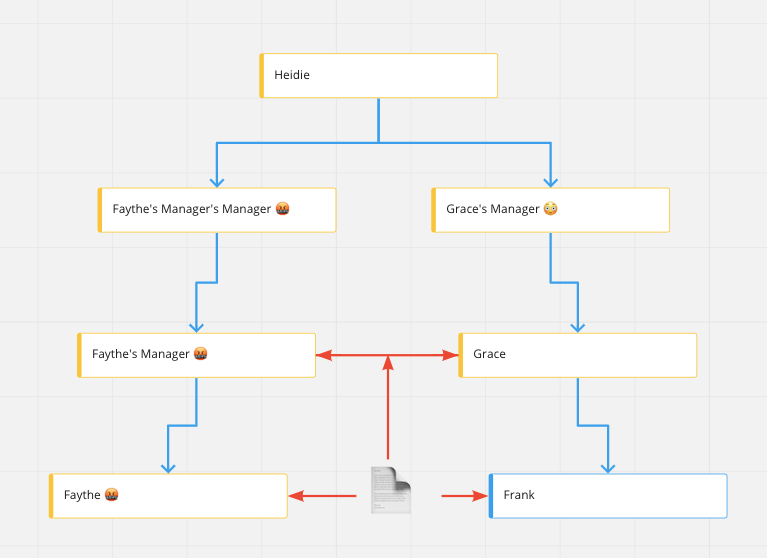

Faythe and Frank are involved in a double escalation. Without discussing the plan for the escalation with Faythe, Frank sends a heated email to just his manager, Grace. Grace goes directly to the VP of engineering, Heidi, skipping several levels of management. Heidi decides in Grace’s favor, and Grace communicates it directly to Frank and Faythe, plus Faythe’s manager.

This is a “dirty” escalation, where the conversation was not properly laddered up on both sides. Faythe may feel like Frank “went over her head”. Faythe is likely to resent the decision and resent Frank. Faythe (and her whole management chain) is probably not happy with Grace. Even Grace’s manager will be surprised if Heidie ever brings this up.

This kind of dirty escalation can happen fast. All it takes is one email, and someone (maybe unintentionally) forgetting to CC someone’s manager. Even if the intention was just to raise visibility, the other party could feel like it was done purposefully to try to increase leverage and drive to a specific outcome. Bad escalations often have this sense of unevenness between the two parties.

Clean Escalations: The One Pager

What would a clean escalation have looked like, in this case?

- Frank and Faythe together draft a short document about their escalation

- Frank and Faythe forward the document to both of their managers

- Repeat

The document should not be drafted by just one person, alone. This can lead to phrasing that puts one person on the defensive. It would not accurately represent both sides.

An escalation document should include a TL;DR statement. It should communicate the one question that needs to be answered. It provides context for people who are less familiar with the situation. At each level, the document should be forwarded to both management chains, together.

Often the mere act of sitting down and trying to write up a proposal will lead to Frank and Faythe to come to a compromise. Partially this is because writing down details forces clarity on the situation. It also reveals options that neither party had thought of independently. A big part of last-minute compromises is that everyone is reluctant to involve their manager, asking for a decision. This makes it more likely that each side will accept a compromise that they would not otherwise have accepted, simply to avoid escalating.

Who to escalate to

Assuming no local compromise can be reached, it’s time for Frank and Faythe to escalate to both of their managers, together. It’s important that an escalation go to the same level on both sides. The goal is for the two new escalated parties to have equal authority. The important thing is to not skip anyone in the management chain. Even if the decision is skipping a level, visibility should not.

Once a decision has been reached, Frank and Faythe need to document what the decision was. This is best done as a new section in the original document. They should also email out a version of the final decision to the involved parties, as well as anyone else who may need a heads up.

Plan for escalation worst-case scenario

It’s possible to anticipate escalations. Any time there is a disagreement between partners in remote parts of the organization, an escalation is likely. The worse case escalation refers to the highest possible person in the organization that an escalation could raise to. For example, an escalation between engineering managers is likely to max out at the VP of Engineering. But, an escalation between an engineering manager and a product manager could go all the way to the CEO. Sometimes just pointing out the worst-case escalation is enough to broker a compromise.

It might make sense to preview a likely escalation to some of the affected higher-ups, to gauge how likely they are to be supportive. But, this needs to be done carefully so that it’s not treated as an escalation, prematurely. It helps to explicitly say “this is not an escalation (yet); no decision is needed right now”.

How to repair a dirty escalation?

If a bad escalation has already happened, it’s possible to bring the situation back under control. One method would be for the original parties to respond by saying that they feel they can resolve the situation themselves. In general, advertising that the issue is being taken off email and back into one-on-one discussion may be enough to stop the escalation. It should be paired with a promise to follow up with an update to the group.